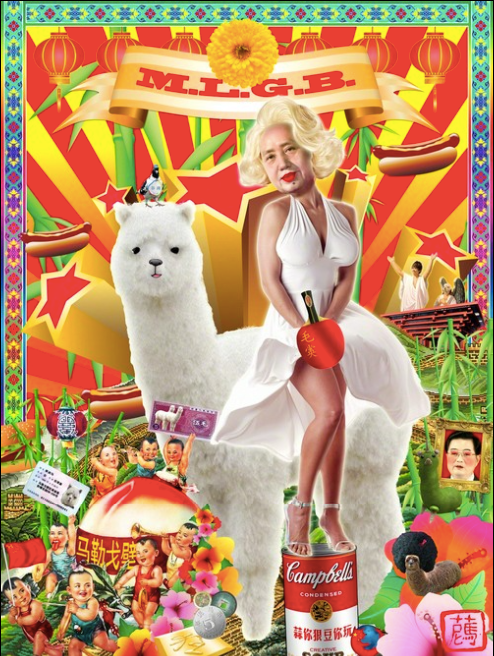

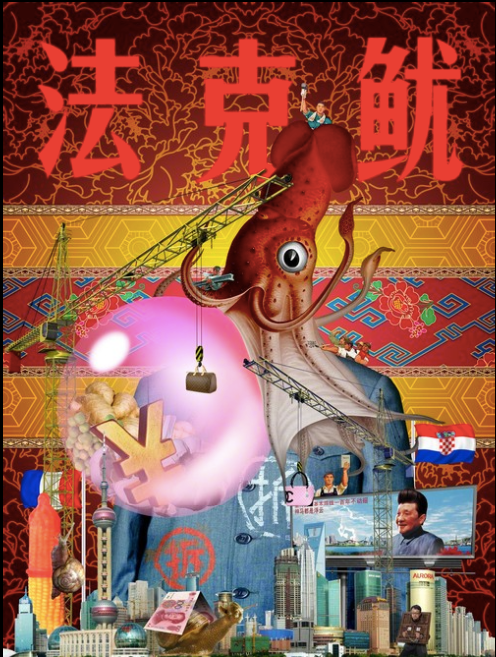

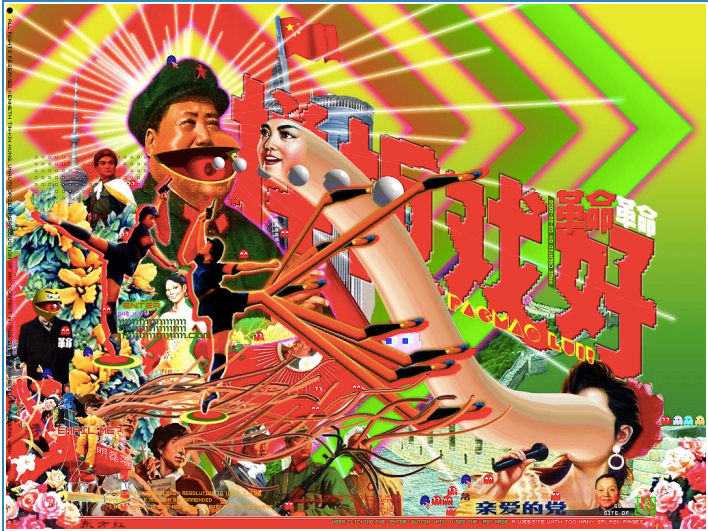

Song of the Grass Mud Horse may seem like a song about a harmless phrase, but many Chinese speakers know the truly NSFW double meaning. It is one of Baidu’s 10 Mythical Creatures, an Internet hoax from 2009 that became a viral meme in China. The other creatures are also plays on words that translate into vulgar profanity, but carry an initially harmless, albeit confusing, image, like the French-Croatian-Squid, Small Elegant Butterfly, Chrysanthemum Silkworms, Singing Rice Goose, and a few others that do not obviously reveal their true profane intentions.

This song has been viral for several years, yet there are plenty of China-philes that are unaware about the nuances and politics of Chinese Internet culture and the rise of these euphemisms. According to China Digital Times, The comparison with the “animal” name is not an actual homophone: the two terms have the same consonants and vowels with different tones, and are represented by different characters. Since Mandarin is a language ripe with homonyms, it is only natural that there are many ways to play on Chinese words. And since the Internet is notorious for being heavily regulated by the government, it is only natural that somehow, Chinese netizens have found ways to poke fun and express themselves in most creative ways.

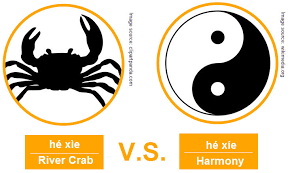

So when and where did these euphemisms start? The answer lies with ex-leader Hu Jintao’s promotion of a “harmonious society” or 和谐社会. 和谐 and 河蟹 are near homonyms, the former meaning harmony and the latter meaning river crab, which you might also recognize from the Cao Ni Ma song. In 2004, the CCP announced that the goal of creating a “harmonious society” would serve as the reason for internet censorship. As a result, Chinese netizens began using the word “harmonious” as a euphemism for censorship, but soon after, that word was also censored. Netizens turned to using “river crab”, a near homophone, as the euphemism for “harmonious” and thus for “censorship”

In 2018, Ai Wei Wei debuted an installation of 3,000 porcelain river crabs, titled He Xie (literally meaning “river crab”). Well known for creating works that critique Chinese society, it is likely that this installation was meant to take a jab at a certain “harmonious society”. The crabs were supposed to represent the artist himself, having in the past felt restricted and controlled by his native country.

By playing with the way a word is used, like as a verb (such as “harmonized”=”river-crabbed”), these euphemisms demonstrate the defiance of Chinese citizens against censorship. However, their widespread use raises the question of what the ultimate goals of this form of expression and rebellion are. So far, it hasn’t been clear if they can actually topple internet censorship or just serve as a temporary diversion until the CCP catches up. As the government continues censoring people, the question remains relevant and obvious.

Additional Sources:

https://chinadigitaltimes.net/space/Grass-mud_horse

https://www.nytimes.com/2009/03/12/world/asia/12beast.html

0 Comments